Thursday, January 31, 2008

Bernie Scheaffer

I was just checking out (Googling) recent articles on Bernie Schaeffer, with whom I've had a lunch or two at the Grand Finale in Glendale and with whom Ken Eisdorfer and I "presented" on utilities next to at the Money Show. This led me to the following article on the five "dirty word" comments made by CNBC and how they are, in a word, fatuous and misleading.

Click on the Title above.

Or:

http://www.marketwatch.com/news/story/five-dirty-words-you-cant/story.aspx?guid=%7B8A8198E2%2DE116%2D4A6F%2DB193%2DFDA8DF7DA262%7D&dist=morenews

Prescient

prescient

One entry found.

prescience

Main Entry: pre·science

Pronunciation: \ˈpre-sh(ē-)ən(t)s, ˈprē-, -s(ē-)ən(t)s\

Function: noun

Etymology: Middle English, from Late Latin praescientia, from Latin praescient-, praesciens, present participle of praescire to know beforehand, from prae- + scire to know — more at science

Date: 14th century

: foreknowledge of events: a: divine omniscience b: human anticipation of the course of events : foresight

— pre·scient \-sh(ē-)ənt, -s(ē-)ənt\ adjective

— pre·scient·ly adverb

Kerviel

The following is from the Globe and Mail. Click on the Title above. Kerviel's 2007 trading was prescient.

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/LAC.20080131.RKERVIEL31/TPStory/Business

What's Missing on CNBC

Quick -- what's missing on CNBC that used to be there for home traders (say in 1987 or 2000 even):

the up and down volume in real time across the bottom

the up and down tics in real time across the bottom

Cramer Last Night

Cramer went all out -- on a limb, that is -- with his huge call that the rally is on and the bottom is in in the stock market.

Tellingly, he said he was buying a house, signalling the end of the housing slide.

His take on the fact that the market cratered after the initial surge after Bernanke's 50 point cut, is "that's just my Wall Street buddies having their fun."

Cramer is so good that you have to want to believe. Frankly, I cannot think of a major "call" of his that was wrong. I do think he thought that the subprime thing was going to be small potatoes, but he quickly changed on this, i.e. with a couple of days.

On natural gas he doesn't have the feel. He forgets about the power of storage, making natural gas hard to game.

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

More Kerviel Discussion

O.K. nobody has answered my basic question:

Kerviel "bet" real euros -- enough to break the bank. He was hedging with "bogus" hedges.

So, what's the counter-party see? A huge bank about to go broke. So where were the "margin calls?" Or, as I suspect, is there a general agreement that "you're good for it," because you are Societe Generale.

Kerviel Today

The implication of all stories is that a BANK can take an unlimited position in billions of euros worth of derivatives. Doesn't that mean any trader can risk the bank's whole existence with a few keystrokes? How many other situations around the world exist like this?

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=awKvzvsr.GmQ&refer=home

Jan. 30 (Bloomberg) -- Jerome Kerviel, the Societe Generale SA trader whose unauthorized bets led to the biggest trading loss in history, told prosecutors the bank cast a ``complacent look'' on his practices.

``As long as we were winning and it wasn't too visible, things worked out, no one said anything,'' Kerviel told police in a transcript cited by Le Monde, which was confirmed by the prosecutors' office. ``I am convinced my managers turned a blind eye to the means and amounts in question.''

Kerviel amassed 50 billion euros ($74 billion) in positions in European stock index futures, whose unwinding resulted in a 4.9 billion-euro loss at France's second-largest bank. Kerviel was charged on Jan. 28 with breach of trust, falsifying documents and hacking into computer systems. He was released from custody after turning in his passport, and was ordered not to leave France, associate with the bank or engage in trading.

In a transcript that draws from 48 hours of interrogation by the financial police, Kerviel provided details of his trades and the subterfuge he used to conceal his deals.

Societe Generale said a routine check exposed one of these bets on Jan. 18. That set in motion a three-day sell-off of his stakes and the bank's Jan. 24 announcement of the losses as a result of the actions of the ``rogue trader.''

Kerviel, 31, cooperated with the bank in explaining his trades, Chief Executive Officer Daniel Bouton said on Jan. 24. Kerviel handed himself over to police on Jan. 26.

`Not a Casino'

Kerviel ``did not have the right to gamble 50 billion euros,'' Societe Generale lawyer Jean Veil said yesterday in an interview on BFM television. ``A bank is not a casino.''

Kerviel joined Societe Generale in 2000, rising to ``trader'' status in 2005. He told investigators that he took his first bet that year, on Allianz SE, calling his 500,000-euro gain a ``jackpot.''

The initial Allianz success created ``a snowball effect,'' said Kerviel, who began creating phoney hedges for his positions. That wasn't hard to do, Kerviel told investigators.

In January 2007, Kerviel said he lost on a position on Germany's DAX Index when the market rose.

``The fake deal went unnoticed because there was no coherent control in January at Societe Generale,'' he said to prosecutors.

`Not Sophisticated'

His job was to arbitrage small price differences between contracts, not to take bets on market directions, Jean-Pierre Mustier, the head of investment banking at Societe Generale, said on a conference call on Jan. 27.

``By Dec. 31, 2007, my cushion was up to 1.4 billion euros, still unreported to the bank,'' Kerviel said.

Convinced the bank would start asking for proof of the fictitious accounts Kerviel said he began faking e-mails. Using skills he gained during his entry-level days at the bank's back office, Kerviel cut and pasted made-up client information into official-looking documents.

``The techniques I used were not at all sophisticated,'' he said during the interrogation.

There were other signs that should have tipped off the bank, he told investigators. On one day in November 2007, he had a gain of 600,000 euros that he refused to explain to his manager. ``Under normal activity-levels, a trader couldn't generate that much cash,'' Kerviel said.

``The simple fact that I didn't take vacation days in 2007 should have alerted my managers,'' he told prosecutors. ``That's one of the first rules of internal controls. A trader who doesn't take vacation is a trader who doesn't want to leave his book to someone else.''

To contact the reporter on this story: Heather Smith in Paris at hsmith26@bloomberg.net

Last Updated: January 30, 2008 00:53 EST

Sunday, January 27, 2008

Societe Generale Explains Today

Click on the Link above and then go to the actual report of Societe Generale.

Only a huge bank can play this game. There should have been margin calls daily on the bank, showing the true situation.

So the explanation doesn't wash.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/27/business/worldbusiness/27cnd-bank.html?hp

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 27, 2008

French Bank Offers Details of Big Loss

By DAVID JOLLY and NICOLA CLARK

PARIS — The French bank Société Générale offered greater detail on Sunday about how it said a low-level former trader carried out fraudulent trades that led to more than $7 billion in losses.

The release of the five-page document came as the accused trader, Jérôme Kerviel, 31, spent a second day in police custody. (Text of the Report, pdf)

Société Générale said Sunday that Mr. Kerviel had misappropriated other people’s computer access codes, falsified documents to enter fictitious trades and employed other methods to cover his tracks helped by his years of experience working in offices that monitor traders.

Until now, the bank, one of Europe’s largest, has insisted that Mr. Kerviel was the lone architect of elaborate trades that involved betting tens of billions of dollars of the bank’s money on European stock index futures. But during a conference call with reporters on Sunday, Jean-Pierre Mustier, chief executive of the bank’s corporate and investment banking arm, said: “I cannot guarantee to you 100 percent that there was no complicity,” The Associated Press reported.

So far, there has been no suggestion that Mr. Kerviel personally profited from the trades.

Talking to reporters Sunday in Paris outside the headquarters of the French financial police, Jean-Michel Aldebert, head of the financial section of the Paris court, said the questioning of Mr. Kerviel had so far been “extremely fruitful.”

He declined to give details of the interrogation, other than to say the trader addressed “the operations that Société Générale described as fictitious.” Mr. Kerviel, he said, had been explaining “what had happened in very interesting ways.”

Mr. Aldebert added that Mr. Kerviel’s state of mind seemed stable. “According to what he told me, he’s doing fine.”

Mr. Aldebert said the court had decided a decision to continue to hold Mr. Kerviel. On Monday, the trader is to be transferred to the main financial judiciary office in Paris, where he will see a judge. Under French law, Kerviel must either be released or face preliminary charges by Monday afternoon.

The Paris prosecutor’s office formally opened an investigation of Mr. Kerviel on Friday after Société Générale filed a complaint accusing him of falsifying bank records and computer fraud. The bank, which says it first uncovered the deals on Jan. 18, was ultimately forced to undo Mr. Kerviel’s trades early last week, leading to losses of 4.9 billion euros, or $7.2 billion, and requiring Société Générale to seek 5.5 billion euros in fresh capital.

The bank’s efforts to release new information appeared to be an attempt to quash widespread speculation that Mr. Kerviel had either exploited weaknesses in the bank’s internal controls or had had an accomplice.

French investigators on Saturday began examining documents and computer files obtained during two raids late on Friday, at Mr. Kerviel’s residence and at the bank offices where he had worked.

A lawyer for Mr. Kerviel, Elisabeth Meyer, could not be reached Sunday for comment. She did not return e-mail messages or answer her phone.

Laura Schalk, a Société Générale spokeswoman, said officers of the financial police had searched the bank’s offices in La Défense, a business district west of Paris, on Friday night. “They were there mostly to collect data from the trader’s electronic files,” she said.

The bank’s management has come under increasing pressure from French officials to come forward with a more detailed accounting of how Mr. Kerviel could have amassed such enormous losses by himself, over the course of a year, without raising any red flags among supervisors or internal auditors.

Daniel Bouton, Société Générale’s chief executive, has said Mr. Kerviel used in-depth knowledge of the bank’s risk-control software systems that he had gained from a previous back-office position. In an interview published Saturday in the French newspaper Le Figaro, Mr. Bouton described Mr. Kerviel’s efforts to hide his activities as being like a “mutating virus.” Mr. Bouton said, “The nature of his fictitious and fraudulent operations were constantly evolving.” He added, “And when the control systems detected an anomaly, he managed to convince control officers that it was nothing more than a minor error.”

At the financial police headquarters in Paris, there was an unusual amount of activity for a Sunday, with police cars coming and going, some with sirens blaring. There are bars on the fourth floor, on the left hand side, on windows of the 10-story building where Mr. Kerviel was being interrogated.

Michel Histel, 62, a retiree who lives nearby and who, like many French people has been avidly following the story, described the scene as “very exceptional.”

“What’s so surprising about this to me is that they brought this young man so quickly to the financial police headquarters,” Mr. Histel said. “What is a little bit revolting to me is that people are attacking this young man.”

“But this bank has been playing with fire for a long time,” he said, referring to Société Générale’s leadership in financial derivatives products.

James Kanter contributed reporting.

Clayton Holdings Story in NYT Today

This is the biggest story of the year to date. Investment banks which used Clayton Holdings are going to go out of business, as their liabilities are astronomical.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 27, 2008

Reviewer of Subprime Loans Agrees to Aid Inquiry

By JENNY ANDERSON and VIKAS BAJAJ

A company that analyzed the quality of thousands of home loans for investment banks has agreed to provide evidence to New York state prosecutors that the banks had detailed information about the risks posed by ill-fated subprime mortgages.

Investigators are looking at whether that information, which could have prevented the collapse of securities backed by those loans, was deliberately withheld from investors.

Clayton Holdings, a company based in Connecticut that vetted home loans for many investment banks, has agreed to provide important documents and the testimony of its officials to the New York attorney general, Andrew M. Cuomo, in exchange for immunity from civil and criminal prosecution in the state.

The agreement, which was confirmed by Mr. Cuomo’s office and Clayton, forwards an investigation by the attorney general into the question of whether the investment banks held back information they should have provided in the disclosures that accompanied the huge packages of loans they offered as securities.

In these disclosures, underwriters typically said that loans that did not meet even lowered lending standards, called exceptions, accounted for a “significant” or “substantial” portion of the loans contained in the securities, but they offered little hard, statistical information that Clayton promised prosecutors it would provide as evidence.

Investment rating firms like Moody’s and Fitch have said that they were deprived of this information before they gave the securities the top rating, triple-A.

Mr. Cuomo has not accused any investment house of a transgression, but he has identified the disclosures of exceptions to the lending standards as the main line of his investigation.

“At the heart of the subprime meltdown is the inability to get information,” said Howard Glaser, a mortgage industry consultant who used to work for Mr. Cuomo when he was secretary of housing and urban development.

About a quarter of all subprime mortgages are in default, which has resulted in billions of dollars in losses for buyers of securities backed by these mortgages. Many of these loans were made with low teaser rates that would later increase.

Critics of these practices say many of these mortgages should never have been made because borrowers could not repay them.

Investment banks, for their part, have said they provided adequate disclosures, and they even kept some of the securities on their books. They have taken more than $100 billion in write-downs as a result.

Mr. Cuomo has already obtained some evidence through subpoenas. But Clayton, which in industry terminology conducts due diligence for the investment banks, could help him identify salient details in its reports.

“The cooperation of compliance officers or due diligence firms is the best cooperation you can get,” said Tamar Frankel, a professor of securities law at Boston University.

In a statement on Saturday, Clayton’s chairman and chief executive, Frank P. Filipps, acknowledged the agreement and said, “We have complied with a subpoena to produce due diligence reports on various pools of loans that we had reviewed for clients and on loans that had exceptions to lenders/seller guidelines and were eventually purchased” by securities issuers. “This information that we provided to the attorney general is the same information that we provided to our clients.”

Without an immunity deal, officials at Clayton could have refused to testify under their right to protect themselves against self-incrimination.

There is no evidence that Clayton did anything wrong, but securing immunity provides legal certainty for the company and its officers. The company is in a difficult position, because its cooperation might hurt its clients, the investment banks.

Clayton, a publicly held company and the nation’s largest provider of mortgage due diligence services to investment banks, communicated daily with bankers putting together mortgage securities.

As part of the deal, Clayton has told the prosecutors that starting in 2005, it saw a significant deterioration of lending standards and a parallel jump in lending exceptions. In an another sign that the industry was becoming less careful, some investment banks directed Clayton to halve the sample of loans it evaluated in each portfolio, a person familiar with the investigation said.

The mortgage business boomed from 2002 to 2006, generating lucrative fees for mortgage brokers, lenders, credit rating firms, investment banks and many investors. Investment banks began buying billions of dollars of more risky loans made to borrowers with blemished, or subprime, credit histories and packaging them into securities that paid high interest.

Among the biggest investment banks in the mortgage business are Lehman Brothers, the Royal Bank of Scotland, Bear Stearns, Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch. None of them have been accused of wrongdoing in Mr. Cuomo’s investigation.

It is unclear how many lending exceptions are contained in the $1 trillion subprime mortgage market, but industry participants cite figures ranging from about 50 percent to 80 percent for some loan portfolios they examined.

The investigation is likely to hinge on whether the reports produced by Clayton included material information, which the issuers of securities must provide to investors under law. Securities fraud cases often turn on courts’ interpretation of materiality.

Investment banks hired companies like Clayton to evaluate a sample, say 20 percent, of the loans. The review was supposed to determine whether the loans complied with the law and met the lending standards that the mortgage companies said they were using. Loans that did not were classified as exceptions.

As demand for the loans surged, mortgage companies were in a strong enough position to stipulate that investment banks have Clayton and other consultants look at fewer loans. The lenders wanted the due diligence to find fewer exceptions, which were sold at a discount, the person familiar with the investigation said.

The investment banks then pooled the mortgages into securities, often by blending loans from different lenders. Information on those mixed pools was then delivered to the rating agencies, which assigned the securities a score. Pension funds and other big investors bought them because they had triple-A ratings.

But investment banks did not give the rating agencies their due diligence reports, and it appears that the agencies did not demand them, people familiar with Mr. Cuomo’s investigation said.

In January 2007, Clayton briefed at least one credit rating agency about the exception reports it was producing, the person involved in the agreement said, but the credit firm did not ask to see the reports.

Last week, the chief executive of Moody’s Investors Service pointed the finger at investment banks. The executive, Raymond W. McDaniel Jr., said in reference to the information the company received, “Both the completeness and veracity was deteriorating.”

Chris Atkins, a spokesman for Standard & Poor’s, said the firm was not responsible for verifying information provided to it by the issuers of securities. It is customary for rating agencies to accept the information they are provided by issuers of securities.

In November, Fitch Ratings published a detailed review of 45 loans in an effort to identify what went wrong as mortgages were turned into securities. It found extensive inaccuracies and fraud. The firm noted that many of the problems would have been easy to identify by looking at loan applications, appraisals and credit reports — but it appears that such review was either never done or ignored. Fitch now says that it will no longer rate subprime mortgage securities unless it is provided access to loan files.

The Clayton agreement is the latest development in Mr. Cuomo’s efforts to uncover abuses in the mortgage business. In November, he sued a subsidiary of First American, a real estate services company, accusing it of inflating appraisals in an effort to secure business from Washington Mutual, the nation’s largest thrift.

Saturday, January 26, 2008

David Muth

I live and work two blocks away from a "young," 61-year-old, lovely man who died January 20, 2008, in Glendale Ohio, after a fight with testicular cancer. My only regret is that I didn't spend more time with him, as our connections were one-timish and business-related. I went to his wake today and met his younger brother Michael, 51, and other family, in from all over the country.

Of course we never know the true nature of such wonderful people unless they are family. There should be a sign posted in front of the homes and businesses of such special men and women who perforce do not promote themselves to the public aggressively: "stop -- you must stop! -- if you have time to meet one of the very best persons on this planet. He will take his busy time to listen and you will be a better person yourself."

The wake was at his business, and that of his wife -- two separate but compatible businesses. The eye-examination room was converted into an impromptu theater which showed on a 21" large Apple screen, a few friends and family-members presenting their thoughts this week. One was an old-time friend who had shared a house when the two were bachelors and before each got married. Well done, well done.

The back room had wonderful food of much variety and Cokes.

Snapshots and paintings by his young, talented wife Merlene were present everywhere, testifying to the lovely man at play with his devoted dogs, on boats on the Ohio River, and otherwise. His professional accomplishments were in the form of helping the handicapped among awards from his peer group.

This wake was so much more meaningful and personal than a church service could have been, as it was in the midst of the place where David and Merlene lived their lives.

"Kerviel, Your Winning Position Risks Too Much"

From the previous article:

Kerviel had been investing the bank's money by hedging on European equity market indices. That means he made bets on how the markets would perform at a future date.

The trader had been betting throughout 2007 that markets would fall. ''He was therefore winning, virtually,''.

But the bank says he had overstepped his authority and was wagering more money than he should have.

So at the beginning of January, Bouton said, the trader voluntarily created losing positions, to neutralize his earlier gains and cover his tracks.

But markets dropped this month, and fast. ''This sad affair veered into a Greek tragedy: His virtual losing position became huge.'

Kerviel Was Winning

Read the following closely. Kerviel was winning but was betting more than authorized. So at the beginning of the year he set up, intentionally, losing positions, to cover his huge positions.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 26, 2008

French Police Search Societe Generale

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 5:55 a.m. ET

PARIS (AP) -- The chief executive of France's second-largest bank insisted in an interview published Saturday that its actions after discovering a trader had cost it billions in a massive fraud scandal did not fuel turmoil on world markets.

Societe Generale was the target of a police search as investigators moved swiftly to sort out what happened.

The bank unsettled the already shaky banking sector when it said that 31-year-old Jerome Kerviel had put tens of billions of dollars at risk in one of history's biggest frauds. The trader also cost the bank more than $7 billion by making bad stock market bets, Societe Generale said.

Skeptics from Kerviel's neighbors to France's prime minister have questioned whether a single futures trader could have managed such large sums. Adding to the mystery, the bank said Kerviel may not have made any personal gain from his unauthorized trades.

The bank said it discovered the fraud last weekend and unwound the trader's losing bets starting Monday, when world markets tumbled. Some analysts have questioned whether Societe Generale exacerbated the fall and indirectly led to the U.S. Federal Reserve's subsequent decision to cut rates.

''It's absurd!'' CEO Daniel Bouton said of the suggestion, in an interview with Le Figaro daily. ''Anyone could calculate our contribution to the market in recent days.''

Bouton was quoted as saying the bank, in closing the trader's unauthorized positions, respected market rules that forbid any player from intervening with sums worth more than 10 percent of a given market. The bank says that is why it took three days to close the positions.

The bank maintains it was the biggest loser in the case, because of the timing of the discovery.

Kerviel had been investing the bank's money by hedging on European equity market indices. That means he made bets on how the markets would perform at a future date.

Bouton said the trader had been betting throughout 2007 that markets would fall. ''He was therefore winning, virtually,'' he said.

But the bank says he had overstepped his authority and was wagering more money than he should have.

So at the beginning of January, Bouton said, the trader voluntarily created losing positions, to neutralize his earlier gains and cover his tracks.

But markets dropped this month, and fast. ''This sad affair veered into a Greek tragedy: His virtual losing position became huge,'' Bouton was quoted as saying.

The bank's systems discovered an anomaly on Jan. 18, he said. At midday that day, a Friday, the trader's positions were neutral, but by the end of trading that day the positions were losing $2.6 billion, Bouton said.

On Sunday, the full scale of the problem was revealed to the bank's management -- ''enormous and totally abnormal,'' Bouton said. ''I decided ... to close the positions and alert the supervisory authorities.''

When Asian and European markets collapsed Monday, ''that had a catastrophic effect. The losses of Societe Generale became even more enormous,'' he was quoted as saying.

Ultimately it took three days to close the positions, and the bank lost $7.2 billion.

Bouton said the overall health of the bank was not at risk, comparing the situation to arson at a factory of a big manufacturer -- a devastating, but one-time, loss.

Asked if the bank could once again be the target of takeover speculation, he said, ''It wouldn't be the first time.''

Financial police searched the bank's headquarters Friday night, said spokeswoman Stephanie Carson-Parker. She gave no other details. Police also searched Kerviel's apartment.

Paris prosecutors are conducting a preliminary investigation based on three complaints: one by the bank accusing 31-year-old Kerviel of fraud, and two by small shareholders. Kerviel's whereabouts are unknown, though his lawyer says he is not fleeing.

French presidential aide Raymond Soubie said the trader had been dealing with more than $73.3 billion. That figure outstrips the bank's market capitalization of $52.6 billion, and is close to the annual GDP of entire nations such Slovakia, Qatar or Libya.

It remains unclear whether Kerviel's actions, if proved, were out of malevolence, ambition or some other reason. Three union officials representing Societe Generale employees said managers at the bank who briefed them about the fraud told them Kerviel was having family problems.

The debacle generated buzz at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and raised questions sector-wide about risk management.

The bank's shares have lost nearly half their value over the past six months. After an up-and-down day Friday, the shares closed down 2.5 percent at $108.62.

The company, which also posted another $2.99 billion subprime-related loss, planned to raise $8.02 billion in new capital.

------

Associated Press writer Cecile Roux in Paris contributed to this report.

Friday, January 25, 2008

Here's Something I Know Something About

Law Firms and The Chargeable Hour. Some are doing away with it because it created unbearable, depressing pressure on the individual lawyer.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 24, 2008

Life’s Work

Who’s Cuddly Now? Law Firms

By LISA BELKIN

IN the last two decades, as working schedules became flexible, and even accounting firms, of all places, embraced the mantra of work-life balance (at least on paper), there was one unbending, tradition-bound profession: the law.

That is why it is so remarkable to watch the legal world racing — metaphorical black robes flapping — to catch up.

Over the last few years and, most strikingly, the last few months, law firms have been forced to rethink longstanding ways of doing business, if they are to remain fully competitive.

As chronicled by my colleague Alex Williams in the Sunday Styles section earlier this month, lawyers are overworked, depressed and leaving.

Less obvious, but potentially more dramatic, are the signs that their firms are finally becoming serious about slowing the stampede for the door. So far the change — which includes taking fresh looks at the billable hour, schedules and partnership tracks — is mostly at the smaller firms. But even some of the larger, more hidebound employers are taking notice.

“There are things happening everywhere, enough to call it a movement,” said Deborah Epstein Henry, who founded Flex-Time Lawyers, a consulting firm that creates initiatives encouraging work-life balance for law firms, with an emphasis on the retention and promotion of women. “The firms don’t think of it as a movement, because it is happening in isolation, one firm at a time. But if you step back and see the whole puzzle, there is definitely real change.”

Last month, Ms. Henry’s ambitious proposal was published in the magazine Diversity and the Bar. Her plan, called FACTS, takes on law-firm bedrock — billable hours, which are how lawyers have calculated their fees for more than 50 years.

At nearly every large American firm, lawyers must meet a quota of hours. During the ’60s and ’70s, the requirement was between 1,600 and 1,800 hours a year or about 34 hours a week, not counting time for the restroom or lunch or water cooler breaks. Today that has risen to 2,000 to 2,200 hours, or roughly 42 hours a week. (Billing 40 hours a week means putting in upward of 60 at the office.)

FACTS is an acronym. Under Ms. Henry’s proposal, work time can be: Fixed (allowing lawyers to choose less high-profile work for more predictable schedules), or Annualized (intense bursts of high-adrenaline work followed by relative lulls); Core (with blocks mapped out for work and for commitments like meeting children at the bus); Targeted (an agreed-upon goal of hours, set annually, customized for each worker, with compensation adjusted accordingly); and Shared (exactly as it sounds).

Ms. Henry’s proposal came at the end of last year, when firms had already started backing away from the billable hour. Some have gone so far as to eliminate it. The Rosen law firm in Raleigh, N.C., one of the largest divorce firms on the East Coast, did so this year, instead charging clients a flat fee.

Similarly, Dreier, a firm with offices in New York and Los Angeles, now pays its lawyers salaries and bonuses based on revenue generation, not hours billed.

At Quarles & Brady, a firm with headquarters in Chicago, not only have billable hour requirements been eliminated, but parental leave has been expanded. Women can now take 12 weeks with pay, men 6 weeks. And that time can be divided, meaning a father can take a few weeks off when his baby is born and a few more after his wife returns to work.

Other firms are making smaller changes. Strasburger & Price, a national firm based in Dallas, announced last October that it was decreasing the hours new associates were expected to log, to 1,600 from 1,920 annually. (Lest you think those lawyers will be able to go home early, however, note that newcomers will now be asked to spend 550 hours a year in training sessions and shadowing senior lawyers.)

Howrey, a global firm in Washington, is tinkering not only with how much associates bill, but also with their pay. Traditionally starting salaries for new lawyers at large firms are all about the same, as are associates’ raises each year.

Beginning this year, Howrey’s starting pay, $160,000, will match the industry average, but further increases will depend on merit, not seniority. This will allow some to reach partnership sooner and others later. It will also allow associates to work at their own pace, with the understanding that a less insane life can be had for a somewhat lower salary.

That is also the message behind changes at Chapman & Cutler, a midsize firm in Chicago, which rolled out a two-tier pay scale in September.

Associates can choose to bill 2,000 hours a year and be paid accordingly. Those who would like to see their families a little more can opt for 1,850 billable hours. Both groups will have a chance to become partner, albeit at different paces. Given the choice, more than half took the reduced schedule.

It should be noted that this is not the first moment when the profession has seemed poised for change. It has been six years since the American Bar Association issued a report calling for the end of the billable hour.

But the law moves slowly, at least when it comes to itself. While change in other fields was driven by pressure from working mothers, it took additional motivating forces for law firms to entertain the idea of reform.

“What is happening now is not just about the needs and demands of women,” said Lauren Stiller Rikleen, who directs the Bowditch Institute for Women’s Success.

Law is responding to a confluence of factors, said Ms. Rikleen, the author of “Ending the Gauntlet: Removing Barriers to Women’s Success in the Law” (Thomson Legalworks, 2006).

First, clients, reacting to spiraling legal costs, have begun insisting on flat-fee deals.

In addition, “you can’t ignore the generational piece,” Ms. Rikleen said. On one end of the spectrum are baby boomers, nearing retirement and mindful of the flexible schedules that did not exist at the start of their careers. At the other end are Gen Y workers, some nearing 30 and in want of a life.

A group of students at Stanford Law School, for instance, shook up the legal world in 2006 when they formed Law Students Building a Better Legal Profession. The Stanford group has more than 130 members, and other elite schools like Yale and New York University have formed chapters. The Stanford organization has published a ranking of firms based on how they treat employees; members vow not to work for those who don’t rate well.

Andrew Bruck, a president of the Stanford group, told the Legal Times: “Just because something always has been doesn’t mean that it always must be.”

A harbinger of changing times might well be the brief filed by the hard-driving white-shoe firm of Weil Gotshal & Manges of New York, asking a judge to reschedule hearings set for Dec. 18, 19, 20 and 27 of last year.

“Those dates are smack in the middle of our children’s winter breaks, which are sometimes the only times to be with our children,” the lawyers wrote.

The judge moved the hearings.

E-mail: Belkin@nytimes.com

The French Rogue Trader

Read this Daily Telegraph article carefully.

http://www.news.com.au/dailytelegraph/story/0,22049,23106253-5006003,00.html

Click on Title. It's possible that one trade on Friday did the whole thing???

Just like the GM Pension guy in 1987 who created the entire crash on Black Monday that year.

Thursday, January 24, 2008

As Soon As Anything Drops Dead

natural gas is produced. Instantaneous.

Oil, on the other hand, takes millions of years to form.

* * * * *

This quote from John McPhee, the best-known "peoples" writer on geology of our country (he writes books, and articles for the New Yorker):

Natural gas is to oil as politicians are to statesmen. Any organic material whatsoever will form natural gas and will form it rapidly, at earth-surface temperatures and on up to many hundreds of degrees. ... "You get natural gas as soon as anything drops dead." For oil, the requisites are the organic material and [a] thermal window [of 50-150 degrees centigrade over millions of years]. John McPhee, In Suspect Terrain, N.Y. Noonday Press, 1991, p.55

Heating Assistance

Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) State Allotments

of $450 Million in Emergency Contingency Funds Reflecting

Low Income Households using Fuel Oil, Propane Gas & Natural Gas for Heat

Total allocation available to the States & Tribes

State Gross Allotments

Alabama $1,288,320

Alaska $3,557,138

Arizona $623,047

Arkansas $983,049

California $6,911,464

Colorado $8,059,412

Connecticut $13,598,024

Delaware $826,638

District of Columbia $488,219

Florida $2,038,508

Georgia $1,611,753

Hawaii $162,313

Idaho $939,987

Illinois $29,100,350

Indiana $13,175,820

Iowa $9,337,881

Kansas $4,288,374

Kentucky $2,050,180

Louisiana $1,317,110

Maine $8,809,352

Maryland $2,407,080

Massachusetts $27,200,551

Michigan $27,628,231

Minnesota $19,904,577

Mississippi $1,104,535

Missouri $11,623,816

Montana $3,687,369

Nebraska $4,617,940

Nevada $292,627

New Hampshire $5,148,509

New Jersey $25,251,481

New Mexico $780,012

New York $82,449,906

North Carolina $2,840,718

North Dakota $4,005,599

Ohio $25,743,608

Oklahoma $1,184,231

Oregon $1,867,706

Pennsylvania $44,287,763

Rhode Island $4,477,366

South Carolina $1,023,189

South Dakota $3,253,247

Tennessee $2,076,788

Texas $3,391,396

Utah $3,745,228

Vermont $3,858,991

Virginia $2,932,092

Washington $3,072,119

West Virginia $1,356,760

Wisconsin $17,916,977

Wyoming $1,499,507

Amount to Territories $203,142

Total $450,000,000

Tribal Set-Aside (included

in total) $4,429,331

ACF Home | Questions? | Site Index | Contact Us | Accessibility | Privacy Policy | Freedom of Information Act | Disclaimers

Department of Health and Human Services | USA.gov: The U.S. government's official web portal

Administration for Children and Families • 370 L'Enfant Promenade, S.W. • Washington, D.C. 20447

Last Updated: January 16, 2008

10 Degrees F. Avg. Temp Today-Tonight

This means it will be a 55 HDD day. Divide by 3. 18 ccf to heat each house. At $1.20 that's $22 per house, or $44, just for today.

What are the people in Western Massachusetts, or New Hampshire, paying today? I'll bet it's $30 per house.

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

Latest Duke Energy Apples to Apples on Natural Gas

I am not sure why Duke refiled this Apples to Apples report again. Last week's appears identical. Search "apples" on this blog and see earlier blog.

Apples chart-related terms, please refer to Chart Definitions that follows the Supplier Plans, Rates, Terms and Conditions section.

The PUCO provides the tools you need to calculate your estimated cost. The Self-Calculation Worksheet that follows Chart Definitions walks you through

the steps needed to manually calculate your own estimated cost. You can also visit www.PUCO.ohio.gov and click on the Apples to Apples link to access the

Apples to Apples Interactive Calculator and automatically calculate your estimated costs.

The Public Utilities Commission of Ohio

Ted Strickland, Governor s Alan R. Schriber, Chairman

180 E. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215-3793 s An Equal Opportunity Employer and Service Provider

Duke Energy Ohio’s (Duke) current total rate is $1.1802 per hundred cubic feet (Ccf), effective from January 02, 2008 to January 30, 2008. This includes a

Gas Cost Recovery (GCR) rate of $0.9044 per Ccf, a gross receipts tax of $0.0442 per Ccf, and transportation costs of $0.2316 per Ccf. Duke’s GCR rate

varies each month and provides a dollar-for-dollar recovery of costs incurred by the local utility to purchase natural gas. The GCR rate allows the local utility to

correct any over or under collections of natural gas costs from previous periods if the actual cost is different than the estimate. Contact information for Duke

Energy Ohio: 139 East Fourth St., Cincinnati, OH 45201, (800) 544-6900, www.duke-energy.com .

Supplier Name Web Page Address Telephone

Integrys Energy Services, Inc. http://www.integrysenergy.com (866) 336-5547

Interstate Gas Supply, Inc. http://www.igsenergy.com (877) 444-7427

Vectren Source http://www.vectrensource.com (800) 516-6740

January 23, 2008

Duke Energy Ohio's Rate

PUCO-

Cramer Yesterday

His Women's Show last night was cunning. Very good audience and interacting.

What a day yesterday, eh? Procter down to 63 at one point. What happens: when bank stocks are weak money goes into Procter. When bank stocks are strong money goes out of Procter. This is the carry trade now for a few weeks. (My opinion; implied by Cramer).

We must give the Bush Administration "catch-up" credit. A crash was averted yesterday.

Sunday, January 20, 2008

Fidelity's Ads on CNBC

There is an ad that has been running on CNBC for over a month which implies that backtesting is a worthwhile exercise for projecting methods for future investment. The regulators should step in. That type of statement is totally misleading, as experience of all traders realize.

Cramer

Thoughts on Cramer's comments on CNBC on Friday, which I have no reason to doubt.

He said if the Bush Administration and Paulson and Bernecke can pull off the bail-out which would avoid the municipal bond crisis looming with the impending failure of mortgage insurers, the Dow will go up 2000 points. If it cannot the Dow will fall 2000 points.

Note how this problem is a municipal bond issue!

Over the weekend two of my friends report they have gotten out of the market, one for Asia and the other into cash totally.

It seems to me this is very rational.

Roofline Comparison (Hot Air)

.jpg)

I have invented the perfect way to project your next winter's heating bill. Just take a picture of the house and look at the roofline!

Friday, January 18, 2008

I Love Paul Krugman

Here's today's column. The import is not good for our economy, but it lays things out so well.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 18, 2008

Op-Ed Columnist

Don’t Cry for Me, America

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Mexico. Brazil. Argentina. Mexico, again. Thailand. Indonesia. Argentina, again.

And now, the United States.

The story has played itself out time and time again over the past 30 years. Global investors, disappointed with the returns they’re getting, search for alternatives. They think they’ve found what they’re looking for in some country or other, and money rushes in.

But eventually it becomes clear that the investment opportunity wasn’t all it seemed to be, and the money rushes out again, with nasty consequences for the former financial favorite. That’s the story of multiple financial crises in Latin America and Asia. And it’s also the story of the U.S. combined housing and credit bubble. These days, we’re playing the role usually assigned to third-world economies.

For reasons I’ll explain later, it’s unlikely that America will experience a recession as severe as that in, say, Argentina. But the origins of our problem are pretty much the same. And understanding those origins also helps us understand where U.S. economic policy went wrong.

The global origins of our current mess were actually laid out by none other than Ben Bernanke, in an influential speech he gave early in 2005, before he was named chairman of the Federal Reserve. Mr. Bernanke asked a good question: “Why is the United States, with the world’s largest economy, borrowing heavily on international capital markets — rather than lending, as would seem more natural?”

His answer was that the main explanation lay not here in America, but abroad. In particular, third world economies, which had been investor favorites for much of the 1990s, were shaken by a series of financial crises beginning in 1997. As a result, they abruptly switched from being destinations for capital to sources of capital, as their governments began accumulating huge precautionary hoards of overseas assets.

The result, said Mr. Bernanke, was a “global saving glut”: lots of money, all dressed up with nowhere to go.

In the end, most of that money went to the United States. Why? Because, said Mr. Bernanke, of the “depth and sophistication of the country’s financial markets.”

All of this was right, except for one thing: U.S. financial markets, it turns out, were characterized less by sophistication than by sophistry, which my dictionary defines as “a deliberately invalid argument displaying ingenuity in reasoning in the hope of deceiving someone.” E.g., “Repackaging dubious loans into collateralized debt obligations creates a lot of perfectly safe, AAA assets that will never go bad.”

In other words, the United States was not, in fact, uniquely well-suited to make use of the world’s surplus funds. It was, instead, a place where large sums could be and were invested very badly. Directly or indirectly, capital flowing into America from global investors ended up financing a housing-and-credit bubble that has now burst, with painful consequences.

As I said, these consequences probably won’t be as bad as the devastating recessions that racked third-world victims of the same syndrome. The saving grace of America’s situation is that our foreign debts are in our own currency. This means that we won’t have the kind of financial death spiral Argentina experienced, in which a falling peso caused the country’s debts, which were in dollars, to balloon in value relative to domestic assets.

But even without those currency effects, the next year or two could be quite unpleasant.

What should have been done differently? Some critics say that the Fed helped inflate the housing bubble with low interest rates. But those rates were low for a good reason: although the last recession officially ended in November 2001, it was another two years before the U.S. economy began delivering convincing job growth, and the Fed was rightly concerned about the possibility of Japanese-style prolonged economic stagnation.

The real sin, both of the Fed and of the Bush administration, was the failure to exercise adult supervision over markets running wild.

It wasn’t just Alan Greenspan’s unwillingness to admit that there was anything more than a bit of “froth” in housing markets, or his refusal to do anything about subprime abuses. The fact is that as America’s financial system has grown ever more complex, it has also outgrown the framework of banking regulations that used to protect us — yet instead of an attempt to update that framework, all we got were paeans to the wonders of free markets.

Right now, Mr. Bernanke is in crisis-management mode, trying to deal with the mess his predecessor left behind. I don’t have any problems with his testimony yesterday, although I suspect that it’s already too late to prevent a recession.

But let’s hope that when the dust settles a bit, Mr. Bernanke takes the lead in talking about what needs to be done to fix a financial system gone very, very wrong.

Thursday, January 17, 2008

Another of My Posts From Last Summer

I wrote:

Wednesday, August 1, 2007

Duke Energy...Hedging

Greg Kearns of Duke Energy's Gas Supply Department graciously called me August 1, 2007 @ 2:35 pm. They have a Hedging Plan which is a "% of base," meaning residential and small commercials. Larger customers take care of themselves and Duke does not have to supply their gas, except for transporting it.

Duke May do 5% 1 year ahead. Committee meets once a month.

Duke is very careful not to fall into a trading mode.

So...Question...What will be the cost of natural gas to the residential user in January? $8.41 (NYMEX futures) + $2.00 for Duke + misc incomprehensible things = $10.60, say. Or, to convert to the way the customer sees it on his bill, $1.06 per ccf.

BUT THAT'S USING THE NYMEX FUTURES, which Duke doesn't trade. (They only buy from their established private sources, which are long-term gas suppliers.)

My guess for next Winter, then... $1.15 per ccf.

=====================

Now I wonder if Duke couldn't have done us a little better.

I'm Raising My Cost of Natural Gas 20% per CCF

Here's what I wrote in November:

Monday, November 19, 2007

There Are Normally 4785 Heating Degree Days a Year

So, divide by three and that's your projected annualized cost of heating your home:

4785/3 = $1,595

(Don't ask why, but it is all spelled out below under "Heating Degree Days."

Based on Duke's filings for January I'm raising my normalized cost $300 to $1,895 on an annual basis -- for one house.

The Dead of Winter

Channel 12 says that their model shows that the True Dead of Winter is today for Cincinnati. Tomorrow the average high starts to go up (normally, but of course not in any given year).

Paulson -- A Different One

It is eery that the former Fed chief is now working for a renowned short-seller of the housing market. However, the following article is not just on that topic, at all:

Trader Made Billions on Subprime

John Paulson Bet Big on Drop in Housing Values;

Greenspan Gets a New Gig, Soros Does Lunch

By GREGORY ZUCKERMAN

January 15, 2008; Page A1

On Wall Street, the losers in the collapse of the housing market are legion. The biggest winner looks to be John Paulson, a little-known hedge fund manager who smelled trouble two years ago.

RELATED ARTICLES

• Greenspan Will Join Paulson

• The Meltdown Mogul of Beverly HillsFunds he runs were up $15 billion in 2007 on a spectacularly successful bet against the housing market. Mr. Paulson has reaped an estimated $3 billion to $4 billion for himself -- believed to be the largest one-year payday in Wall Street history.

Now, in another twist in financial history, Mr. Paulson is retaining as an adviser a man some blame for helping feed the housing-market bubble by keeping interest rates so low: former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. (See article.)

On the way to his big score, Mr. Paulson did battle with a Wall Street firm he accused of trying to manipulate the market. He faced skepticism from other big investors. At the same time, fearing imitators, he used software that blocked fund investors from forwarding his emails.

One thing he didn't count on: A friend in whom he had confided tried the strategy on his own -- racking up huge gains himself, and straining their friendship. (See article.)

Like many legendary market killings, from Warren Buffett's takeovers of small companies in the '70s to Wilbur Ross's steelmaker consolidation earlier this decade, Mr. Paulson's sprang from defying conventional wisdom. In early 2006, the wisdom was that while loose lending standards might be of some concern, deep trouble in the housing and mortgage markets was unlikely. A lot of big Wall Street players were in this camp, as seen by the giant mortgage-market losses they're disclosing.

"Most people told us house prices never go down on a national level, and that there had never been a default of an investment-grade-rated mortgage bond," Mr. Paulson says. "Mortgage experts were too caught up" in the housing boom.

In several interviews, Mr. Paulson made his first comments on how he made his historic coup. Merely holding a different opinion from the blundering herd wasn't enough to produce huge profits. He also had to think up a technical way to bet against the housing and mortgage markets, given that, as he notes, "you can't short houses."

Also key: Mr. Paulson didn't turn bearish too early. Some close students of the housing market did just that, investing for a downturn years ago -- only to suffer such painful losses waiting for a collapse that they finally unwound their bearish bets. Mr. Paulson, whose investment specialty lay elsewhere, turned his attention to the housing market more recently, and got bearish at just about the right time.

Word of his success got around in the world of hedge funds -- investment partnerships for institutions and rich individuals. George Soros invited Mr. Paulson to lunch, asking for details of how he laid his bets, with instruments that didn't exist a few years ago. Mr. Soros is famous for another big score, a 1992 bet against the British pound that earned $1 billion for his Quantum hedge fund. He declined to comment.

Mr. Paulson, who grew up in New York's Queens borough, began his career working for another legendary investor, Leon Levy of Odyssey Partners. Now 51 years old, Mr. Paulson benefited from an earlier housing slump 15 years ago, buying a New York apartment and a large home in the Hamptons on Long Island, both in foreclosure sales.

After Odyssey, Mr. Paulson -- no relation to the Treasury secretary -- became a mergers-and-acquisitions investment banker at Bear Stearns Cos. Next he was a mergers arbitrager at Gruss & Co., often betting on bonds to fall in value.

In 1994 he started his own hedge fund, focusing on M&A. Starting with $2 million, he built it to $500 million by 2002 through a combination of its returns and new money from investors. After the post-tech-bubble economic slump, he bought up debt of struggling companies, and profited as the economy recovered. His funds, run out of Manhattan offices decorated with Alexander Calder sculptures, did well but not spectacularly.

Auto Suppliers

By 2005, Mr. Paulson, known as J.P., worried that U.S. economic strength would flag. He began selling short the bonds of companies such as auto suppliers, that is, betting on them to fall in value. Instead, they kept rising, even bonds of companies in bankruptcy proceedings.

"This is crazy," Mr. Paulson recalls telling an analyst at his firm. He urged his traders to find a way to protect his investments and profit if problems developed in the overall economy. The question he posed to them: "Where is the bubble we can short?"

They found it in housing. Upbeat mortgage specialists kept repeating that home prices never fall on a national basis or that the Fed could save the market by slashing interest rates.

One Wall Street specialty during the boom was repackaging mortgage securities into instruments called collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs, then selling slices of these with varying levels of risk.

For buyers of the slices who wanted to insure against the debt going bad, Wall Street offered another instrument, called credit-default swaps.

Naturally, the riskier the debt that such a swap "insured," the more the swap would cost. And this price would go up if default risk appeared to be increasing. This meant an investor of a bearish bent could buy the swaps as a way to bet on bad news happening.

During the boom, however, many were so blind to housing risk that this "default insurance" was priced very cheaply. Analyzing reams of data late at night in his office, Mr. Paulson became convinced investors were far underestimating the risk in the mortgage market. In betting on it to crumble, "I've never been involved in a trade that had such unlimited upside with a very limited downside," he says.

Paulo Pelligrini, a portfolio manager at Paulson & Co., began to implement complex debt trades that would pay off if mortgages lost value. One trade was to short risky CDO slices.

Another was to buy the credit-default swaps that complacent investors seemed to be pricing too low.

"We've got to take as much advantage of this as we can," Mr. Paulson recalls telling a colleague around the middle of 2005, when optimism about the housing market was at its peak.

His bets at first were losers. But lenders were getting less and less rigorous about making sure borrowers could pay their mortgages. Mr. Paulson's research told him home prices were flattening. Suspecting that rating agencies were too generous in assessing complex securities built out of mortgages, he had his team begin tracking tens of thousands of mortgages. They concluded it was getting harder for lenders to collect.

His confidence rose in January 2006. Ameriquest Mortgage Co., then the largest maker of "subprime" loans to buyers with spotty credit, settled a probe of improper lending practices by agreeing to a $325 million payment. The deal convinced Mr. Paulson that aggressive lending was widespread.

He decided to launch a hedge fund solely to bet against risky mortgages. Skeptical investors told him that others with more experience in the field remained upbeat and that he was straying from his area of expertise. Mr. Paulson raised about $150 million for the new fund, largely from European investors. It opened in mid-2006 with Mr. Pelligrini as co-manager.

Adding to the Bet

Housing remained strong, and the fund lost money. A concerned friend called, asking Mr. Paulson if he was going to cut his losses. No, "I'm adding" to the bet, he responded, according to the investor. He told his wife "it's just a matter of waiting," and eased his stress with five-mile runs in Central Park.

"Someone from more of a trading background would have blown the trade out and cut his losses," says Peter Soros, a George Soros relative who invests in the Paulson funds. But "if anything, the losses made him more determined."

Investors had recently gained a new way to bet for or against subprime mortgages. It was the ABX, an index that reflects the value of a basket of subprime mortgages made over six months. An index of those made in the first half of 2006 appeared in July 2006. The Paulson funds sold it short.

The index weakened in the second half. By year end, the new Paulson Credit Opportunities Fund was up about 20%. Mr. Paulson started a second such fund.

On Feb. 7, 2007, a trader ran into his office with a press release: New Century Financial Corp., another big subprime lender, projected a quarterly loss and was restating prior results.

Once-complacent investors now began to worry. The ABX, which had begun with a value of 100 in July 2006, fell into the 60s. The new Paulson funds rose more than 60% in February alone.

But as his gains piled up, Mr. Paulson fretted that his trades might yet go bad. Based on accounts of barroom talk and other chatter by a Bear Stearns trader, he became convinced that Bear Stearns and some other firms planned to try to prop the market for mortgage-backed securities by buying individual mortgages.

Adding to his suspicions, he heard that Bear Stearns had asked an industry group to codify the right of an underwriter to modify or buy out a faltering pool of loans on which a mortgage security was based. Mr. Paulson claimed this would "give cover to market manipulation." He hired former Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Harvey Pitt to spread the word about this alleged threat.

In the end, Bear Stearns withdrew the proposal. It was merely about clarifying "our right to continue to service loans -- whether that be modifying loans when people can't pay their mortgage or buying out loans when rep and warranty issues are involved in the underwriting process," says a Bear Stearns spokesman.

Events at Bear Stearns soon added to the worries: Two Bear Stearns hedge funds that invested in subprime mortgages collapsed in mid-2007. Suddenly, investors began to shun such mortgages.

As Mr. Paulson's funds racked up huge gains, some of his investors began telling others about the funds' tactics. Mr. Paulson was furious, worried that others would steal his thunder. He began using technology that prevented clients from forwarding his emails.

In the fall, the ABX subprime-mortgage index crashed into the 20s. The funds' bet against it paid off richly.

Credit-default swaps that the funds owned soared, as investors' perception of risk neared panic levels and they clamored for this insurance.

And the debt slices the funds had bet would lose value, indeed fell -- to nearly worthless.

Debt Protection

One concern was that even if Mr. Paulson bet right, he would find it hard to cash out his bets because many were in markets with limited trading. This hasn't been a problem, however, thanks to the wrong bet of some big banks and Wall Street firms. To hedge their holdings of mortgage securities, they've scrambled to buy debt protection, which sometimes means buying what Mr. Paulson already held.

The upshot: The older Paulson credit funds rose 590% last year and the newer one 350%.

Mr. Paulson has tried to keep a low profile, saying he's reluctant to celebrate while housing causes others pain. He has told friends he'll increase his charitable giving. In October, he gave $15 million to the Center for Responsible Lending to fund legal assistance to families facing foreclosure. The center lobbies for a law that would let bankruptcy judges restructure some mortgages.

Helping Homeowners

"While we never made a subprime loan and are not predatory lenders, we think a lot of homeowners have been victimized," Mr. Paulson says. "Bankruptcy is the best way to keep homeowners in the home without costing the government any money."

The bill, besides helping borrowers, could help the Paulson funds' bearish mortgage bets. If the result was that judges lowered monthly payments on some mortgages, their market value could fall. Mr. Paulson says it's far from certain his funds would benefit. The center says that none of the $15 million will be used to lobby.

Mr. Paulson, who was already worth over $100 million before his windfall, isn't changing his routine much. He still gets to his Manhattan office early -- wearing a dark suit and a tie, unlike many hedge-fund operators -- and leaves around 6 p.m. for the short commute to his East Side townhouse.

One thing is different: It's easy to attract investors now. The firm began 2007 managing $7 billion. Investors have poured in $6 billion more in just the past year. That plus the 2007 investment gains have boosted the total his fund firm manages to $28 billion, making it one of the world's largest.

Mr. Paulson has taken profits on some, but not most, of his bets. He remains a bear on housing, predicting it will take years for home prices to recover. He's also betting against other parts of the economy, such as credit-card and auto loans. He tells investors "it's still not too late" to bet on economic troubles.

At the same time, he's looking to the next turn in the cycle. In a recent investor presentation, he said his firm would at some point "start preparing" for opportunities in troubled debt.

Write to Gregory Zuckerman at gregory.zuckerman@wsj.com

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

Just Now -- Duke's Apples to Apples Filed

Calculator and automatically calculate your estimated costs.

The Public Utilities Commission of Ohio

Ted Strickland, Governor s Alan R. Schriber, Chairman

180 E. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215-3793 s An Equal Opportunity Employer and Service Provider

Duke Energy Ohio’s (Duke) current total rate is $1.1802 per hundred cubic feet (Ccf), effective from January 02, 2008 to January 30, 2008. This includes a

Gas Cost Recovery (GCR) rate of $0.9044 per Ccf, a gross receipts tax of $0.0442 per Ccf, and transportation costs of $0.2316 per Ccf. Duke’s GCR rate

varies each month and provides a dollar-for-dollar recovery of costs incurred by the local utility to purchase natural gas. The GCR rate allows the local utility to

correct any over or under collections of natural gas costs from previous periods if the actual cost is different than the estimate. Contact information for Duke

Energy Ohio: 139 East Fourth St., Cincinnati, OH 45201, (800) 544-6900, www.duke-energy.com .

Supplier Name Web Page Address Telephone

Integrys Energy Services, Inc. http://www.integrysenergy.com (866) 336-5547

Interstate Gas Supply, Inc. http://www.igsenergy.com (877) 444-7427

Vectren Source http://www.vectrensource.com (800) 516-6740

January 16, 2008

D

Oil is Above $9 per Million BTU So Adjust the Last Chart Accordingly

http://www.economagic.com/em-cgi/data.exe/doeme/d2rcaus

GCR of Duke Going Back to 1996 to 1999

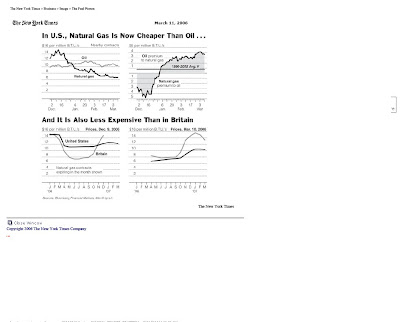

New York Times From Two Years Ago

The situation two years ago remains true today, perhaps even more so. Natural gas has not risen to match the increase in oil.

So natural gas is by far the best deal to the residential user in Ohio. And probably elsewhere.

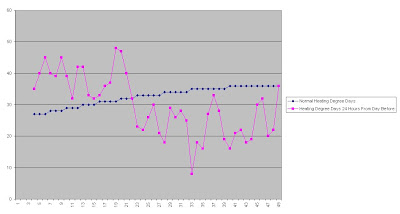

Two Years Ago Chart Showing Real Warming

Compared to normal. This chart was prepared January 18, 2006, almost exactly two years ago to today's date of January 16, 2008.

This weekend we are about to Real Cold, so the upcoming chart will show the line going well above of normal for at least a week, perhaps, beginning Saturday, January 19th.

With the relatively high cost of natural gas, the implications for the Midwest are bad enough. The implications for northeast are staggering. Oil and Propane is the source of heat. The poor people in Massachusetts and New Hampshire!

Monday, January 14, 2008

Now Thru Jan 26th is Normally Coldest

With an average of 36 Heating Degree Days each day.

Weather is projected to drop precipitously this coming weekend for a few days. If it goes to 60 HDD, each house will cost about $25 per day to heat. Greenville and Laurel. Both are pretty fully heated, Greenville because kitchen work is being done by three workmen.

Duke Bill December Usage Greenville

Duke Bill December Usage Laurel Avenue

Saturday, January 12, 2008

Pretty Good One re the Dollar, the Euro and the Pound

For those who travel to Europe, a friend of a friend of mine said:

"Prices are about the same in all three cities now. It cost 100 euros in Paris; 100 pounds in London; 100 dollars in New York."

Banc of America -- The Worst Bet Ever?

Those of us who have seen Mazilo on CNBC, deep tan and all -- there's no way Countrywide isn't indicted as a company, a la Arthur Anderson in Enron. If that happens, of course, the Banc of America deal is the Worst Bet Ever.

Civil Society -- Bush and Congress Scrambling for Fiscal Program

Bush could greatly help his legacy if he co-operates with Congress pronto, which looks like is happening. NYT today has an article on this. I hope the Democrats do not screw it up but it looks like they won't.

Best Cramer in a while, with a very specific Game Plan for next week.

Thursday, January 10, 2008

Ah Enron

Click on Link or cut and paste the following to get that special "Enron" feeling.

http://images.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://www.ecotao.com/holism/add/enron/Enron_whole.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.ecotao.com/holism/add/enron/Enron.html&h=468&w=743&sz=53&tbnid=DiuEpGmPwn4ifM:&tbnh=89&tbnw=141&prev=/images%3Fq%3Denron%26um%3D1&start=3&sa=X&oi=images&ct=image&cd=3

Cost Per Megawatt

Last summer I wrote what I felt was true. Now, after going on line at the Ohio Public Utilities Commission, I realize this is not true. The cost is $2.6 billion. This has huge implications for the rebuilding of our infrastructure in this country.

It's because of the demand for product by China, India, etc.

"Saturday, June 16, 2007

1000 Megawats of Power Costs $1 Billion-- New Coal-Fired Base Load Plant

Increase in MW Load Per Degree-Fahrenheit Increase, By System:

Duke Energy, Cinergy Division (Cincinnati) 300

DP&L (Dayton) 44"

Civil Society

January 8, 2008, 9:19 am

A Litigator’s Nightmare: Late Filing Costs Client $1 Million

Posted by Peter Lattman

It’s a litigator’s worst dream — costing your client serious money by missing a filing deadline.

That nightmare was a reality for MoFo and another small SoCal firm, which appears to have cost its client Toshiba America $1 million when it was one-minute late — 1 minute! — in filing a motion for attorneys fees. (The nightmare was first reported by the Daily Journal.) A judgment in favor of MoFo’s client was entered on Sept. 26, giving Toshiba’s attorneys 14 days - until Oct. 10 - to file their attorneys-fees motion. Here are the relevant paragraphs straight from Judge Cormac Carney’s opinion. For anyone who has stared in the face of a filing deadline, this might make your choke on your Cheerios:

Here, [Toshiba’s] purported reason for its delay is that its courier was caught in traffic at 3:30 in the afternoon in Santa Ana, California. Mr. Mersel, attorney for [Toshiba], asserts that he waited until 3:14 p.m. on the last day of the filing period to deliver the motion to Morrison & Foerster’s regular courier service. Mr. Mersel asserts that although he was aware that the filing deadline was 4:00 p.m., he had “never had a problem with getting papers filed by 4:00 p.m. when delivering them to the attorney service” forty-five minutes in advance. The courier, Mr. Moskus, swiftly responded to Mr. Mersel’s request, leaving on his motorcycle for the courthouse at approximately 3:30 p.m. Unfortunately, Mr. Moskus encountered “unusually heavy traffic” and had to “wait at the railroad crossing on Grand Avenue for a long train to pass.” Consequently, Mr. Moskus arrived at the Courthouse after the office had closed and Mr. Mersel was unable to file the motion until the following day, on October 11, 2007.

These circumstances, however regrettable, do not meet the standard for “excusable neglect.” Although the delay was not lengthy and it does not appear that [defendant] was prejudiced by it, the reason for the delay was entirely within [Toshiba’s] control and [Toshiba] has not offered a good faith reason for the delay.

Concluded the judge: “[T]he entirely foreseeable obstacle of traffic in Southern California in the late afternoon . . . cannot justify an enlargement of time.”

The Law Blog contacted Mark Mersel, who left MoFo for Bryan Cave last week. He responded in an email that “the client has asked us not to comment.” Dean Zipser, MoFo’s Orange County managing partner who oversaw the litigation, did not respond to a request of comment.

Civil Society

This is also worthy of a close read. How could the pollsters get it so wrong?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 10, 2008

Op-Ed Contributor

Getting It Wrong

By ANDREW KOHUT

Washington

THE failure of the New Hampshire pre-election surveys to mirror the outcome of the Democratic race is one of the most significant miscues in modern polling history. All the published polls, including those that surveyed through Monday, had Senator Barack Obama comfortably ahead with an average margin of more than 8 percent. These same polls showed no signs that Senator Hillary Clinton might close that gap, let alone win.

While it will take time for those who conducted the New Hampshire tracking polls to undertake rigorous analyses of their surveys, a number of things are immediately apparent.

First, the problem was not a general failure of polling methodology. These same pollsters did a superb job on the Republican side. Senator John McCain won by 5.5 percent. The last wave of polls found a margin of 5.3 percent. So whatever the problem was, it was specific to Mrs. Clinton versus Mr. Obama.

Second, the inaccuracies don’t seem related to the subtleties of polling methods. The pollsters who overestimated Mr. Obama’s margin ranged from CBS and Gallup (who have the most rigorous voter screens and sampling designs, and have sterling records in presidential elections) to local and computerized polling operations, whose methods are a good deal less refined. Everyone got it wrong.

Third, the mistakes were not the result of a last-minute trend going Mrs. Clinton’s way. Yes, according to exit polls the 17 percent of voters who said they made their decision on Election Day chose Mrs. Clinton a little more than those who decided in the past two or three weeks. But the margin was very small — 39 percent of the late deciders went for Mrs. Clinton and 36 percent went for Mr. Obama. This gap is obviously too narrow to explain the wide lead for Mr. Obama that kept showing up in pre-election polls.

Fourth, some have argued that the unusually high turnout may have caused a problem for the pollsters. It’s possible, but unlikely. While participation was higher than in past New Hampshire primaries, the demographic and political profile of the vote remains largely unchanged. In particular, the mix of Democrats to independents — 54 percent to 44 percent respectively — is close to what it was in 2000, the most recent New Hampshire primary without an incumbent in the race.

To my mind all these factors deserve further study. But another possible explanation cannot be ignored — the longstanding pattern of pre-election polls overstating support for black candidates among white voters, particularly white voters who are poor.

In exploring this factor, it is useful to look closely at the nature of the constituencies for the two candidates in New Hampshire, which were divided along socio-economic lines.

Mrs. Clinton beat Mr. Obama by 12 points (47 percent to 35 percent) among those with family incomes below $50,000. By contrast, Mr. Obama beat Mrs. Clinton by five points (40 percent to 35 percent) among those earning more than $50,000.

There was an education gap, too. College graduates voted for Mr. Obama 39 percent to 34 percent; Mrs. Clinton won among those who had never attended college, 43 percent to 35 percent.

Of course these are not the only patterns in Mrs. Clinton’s support in New Hampshire. Women rallied to her (something they did not do in Iowa), while men leaned to Mr. Obama. Mrs. Clinton also got stronger support from older voters, while Mr. Obama pulled in more support among younger voters. But gender and age patterns tend not to be as confounding to pollsters as race, which to my mind was a key reason the polls got New Hampshire so wrong.

Poorer, less well-educated white people refuse surveys more often than affluent, better-educated whites. Polls generally adjust their samples for this tendency. But here’s the problem: these whites who do not respond to surveys tend to have more unfavorable views of blacks than respondents who do the interviews.

I’ve experienced this myself. In 1989, as a Gallup pollster, I overestimated the support for David Dinkins in his first race for New York City mayor against Rudolph Giuliani; Mr. Dinkins was elected, but with a two percentage point margin of victory, not the 15 I had predicted. I concluded, eventually, that I got it wrong not so much because respondents were lying to our interviewers but because poorer, less well-educated voters were less likely to agree to answer our questions. That was a decisive factor in my miscall.

Certainly, we live in a different world today. The Pew Research Center has conducted analyses of elections between candidates of different races in 2006 and found that polls now do a much better job estimating the support for black candidates than they did in the past. However, the difficulties in interviewing the poor and the less well-educated persist.

Why didn’t this problem come up in Iowa? My guess is that Mr. Obama may have posed less of a threat to white voters in Iowa because he wasn’t yet the front-runner. Caucuses are also plainly different from primaries.

In New Hampshire, the ballots are still warm, so it’s hard to pinpoint the exact cause for the primary poll flop. But given the dearth of obvious explanations, serious consideration has to be given to the difficulties that race and class present to survey methodology.

Andrew Kohut is the president of the Pew Research Center.

Civil Society

The point raised in the following article is the major "take-home" from the New Hampshire primary. Missed by the pundits on TV, I believe.

January 9, 2008, 4:02 pm

A 60,000-Vote Differential

By Ron Klain

Some observers, including David Brooks , have looked at the New Hampshire primary results and concluded that “roughly equal” numbers of votes were recorded in the Republican and Democratic primaries. But I see a huge difference in the numbers — differences of historical significance, in fact.

The four Democratic candidates last night drew about 270,000 votes between them, while the larger G.O.P. field drew about 210,000, or about 60,000 more votes for the Democrats than the Republicans. Maybe this sounds like a small difference to some, but given that fewer than 700,000 New Hampshirites voted in the last general election for president, a 60,000-vote differential in that small state is quite significant.

And even this relative measure fails to capture what a historic night it was for Democrats in New Hampshire.